“My architecture is in no sense conceived in plans, but instead in spaces (cubes). I do not design any floor plans, facades, cross-sections. I design spaces. For me, there is no ground floor, upper floor etc… For me, it is only about contiguous, continual spaces, rooms, bestibules, terraces etc. Floors mix with each other and spaces meet up with each other. Each space demands a different height: the dining room is, after all, higher than the larder, hence the ceilings are laid at different levels. To connect these spaces so that the rising and descending was not only unnoticeable but also even purposeful: in this there lies, as I see it, for others a great secret, but for me only what is self-evident.”

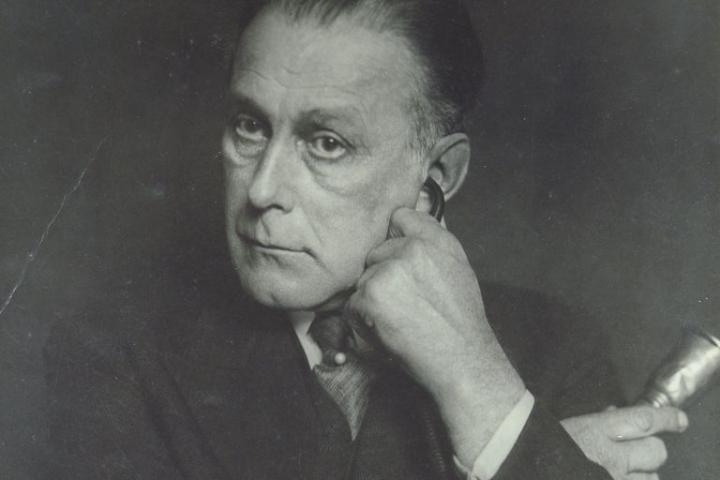

In 1870, in the city of Brno, one of the most important of Europe’s twentieth-century architects was born: Adolf Loos. He studied in Liberec and also at the Vienna Technical University, yet never completed any of his study programs. Eventually, he left for a stay in the USA, where he had the opportunity to gain knowledge of the style of Louis Sullivan (1856-1924), the chief figure of the “Chicago School” in architecture. By the mid-1890s, he had settled in Vienna, where he worked first under architect Karl Mayderer (1856-1935), and one year later started an independent practice in his own design office.

A key milestone for Loos came in 1908, with the publication of his most widely cited essay Ornament and Crime, in which he wrote: “I have reached the following knowledge and present it to the world: The evolution of culture is the same as the removal of ornament from items of daily use. I thought that this would bring the world a new joy, yet it gave me no thanks for it. People were sad, and their heads drooped: burdened by the knowledge that one could no longer create any new ornament.”

During the same year, Loos completed the realisation of the American Bar (Kärntner Bar) in Vienna, where he achieved an exceptional combination of luxurious materials and simplified details. A few years later, in 1911, Loos sparked much angry debate among his fellow-Viennese with the construction of a new building on Michaelerplatz. The department store for the tailoring firm Goldman & Salatsch, it irked many observers with its austere form, lack of any decoration, and no less its position directly across from the Hofburg, then the seat of the ruling Habsburg dynasty and Emperor Franz Josef II. “But the objection that I, indeed I myself was guilty of a crime against this image of the historic city, wounded me more sorely than many would have thought. Indeed, I had designed the building to conform, as much as possible, to its surroundings. (…) As a result, I was faced with the task of strictly separating the commercial building and the residential one.”

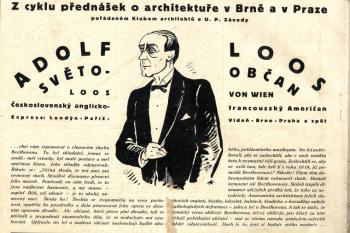

Loos made his first public appearance in Prague in 1911, giving a lecture on the subject of “Ornament and Crime” in the Polytechnische-Gesellschaft of the German Technical University. This period, however, marked the culminating point of Czech architectural Cubism, hence the Czech-language press unfortunately had little to say about Loos’s lecture. Not long after the completion of the building on Michaelerplatz, Loos opened his private architectural school. His pedagogic method was grounded in students engaging in mutual comparison of their work, thus learning directly from one another. Within a single project, he discussed all technical and architectonic details, teaching his pupils to form the projects for buildings from the inside outward: floors and ceilings were given primary importance, and only then was the façade discussed. In this way, Loos hoped to ensure his students could think in three dimensions, in ‘cubes’. “Very few architects can do this today. It seems that the teaching of architecture ends on the surface.”

After World War I, Adolf Loos and his pupil Paul Engelmann created the design for the Villa Konstandt in Olomouc, a five-storey villa with fourteen separate height levels. At the end of October 1920, Loos and his then wife, the dancer Elsie, returned from Paris to Vienna. In the late 1920s, Loos worked extensively in Prague, where he created one of his greatest realisations: the Villa Müller in the suburb of Střešovice, where for once Loos brought his idea of the Raumplan to full perfection. His later works in the Czech lands include commissions in Plzeň, before his death in 1933 in a sanatorium outside Vienna.

(Alena Havlíková)