Adolf Loos (1870 –1933) was one of the first architects to think and act as a true “European” throughout his whole life. Born in Brno during the Habsburg Monarchy, he began to learn construction crafts even as a child in his father’s sculpting and stonecutting workshop. He completed his formal education at the technical school in Liberec (then Reichenberg), specialising in building techniques. Afterwards, he also studied architecture in Dresden. However, it was mostly through his own observations gathered during a three-year long stay in the United States that he learned the most. These years turned out to be the most important and formative time in his early life. In Vienna, he launched his career as an incisive writer and commentator, as well as a draftsman in an interior design company. His essays, often critical reviews of current events and exhibitions, became widely known due to his trenchant style. One of his most enthusiastic readers was a wealthy entrepreneur from Pilsen, Otto Beck. He was not only to become Loos’s father-in-law in a couple of years, but was also a shareholder in a plant that belonged to another future client of Loos in Pilsen, Wilhelm “Willy” Hirsch.

Once Loos became widely known in Vienna through his writing, he started to execute a long series of construction designs, which continued to be realised in the city throughout the rest of his life. However, as a “European” architect, he was not limited to the capital where he resided. Soon, he was also overseeing projects in Switzerland, Berlin, Prague, Paris, and Poland. It was only logical that after the fall of the monarchy, he refused to respond to the authorities’ call for former Czechoslovak citizens to choose either Austria or Czechoslovakia as their future country of domicile. As he simply ignored the bureaucratic restrictions, he was, after the deadline to choose one or the other had passed, officially made a Czechoslovak citizen and lost his Austrian citizenship. Yet, this did not mean that he left Austria, or what remained of it – at least not for the next couple of years. In fact, his Czechoslovak passport made it easier for him to indulge in his lifelong desire to travel after the end of the war. As a lecturer he toured Europe, and received many new commissions as the economy recovered. In 1924, after a dispute with Vienna town hall officials over fundamental issues concerning general building policy, Loos moved to France. Paris and the Côte d’Azur became the favourite places for his creative work, interrupted by longer sojourns in Czechoslovakia, Austria, Switzerland, and Germany. He also travelled to England, Greece, Italy, as well as North Africa. Due to deteriorating health, he spent his last years in various sanatoriums, but he never completely gave up his work. He died in 1933 in Kalksburg near Vienna, where his career had started almost forty years earlier.

PILSEN AND THE FAMILY OF MARTHA AND WILHELM HIRSCH

Wilhelm Hirsch and Otto Beck co-owned a wire manufacturing company in Pilsen, founded by Wilhelm’s father Richard. The factory primarily focused on the production of wire mesh, barbed wire, equipment for sanding parquet flooring, and closures for bags. Furthermore, the line also included roofing materials such as storm brackets, ridge hooks, and roofing pegs. Private galvanising and pewtering facilities were part of the plant complex. The Hirsch factory exports travelled as far as Great Britain and the United States. With this solid financial and social background, Hirsch was a member of the local wealthy upper middle class, as well as the German Free Mason Lodge. In 1907, he hired Loos to design a magnificent and well-appointed apartment that would emphasise the social status of the Hirsch family.

Loos had shown several of his realised works to his Pilsner friend Willy Hirsch, including apartments designed for Alfred Kraus (brother of the journalist and dramatist Karl Kraus) and Rudolf Kraus two years earlier. The young but already quite well-known architect had been organising a number of guided tours for potential patrons through his completed apartments and houses. Such tours and visits often played a crucial role in obtaining commissions, and they certainly encouraged Willy Hirsch to entrust the reconstruction of his apartment to Loos. In February 1907, the architect was finally invited by the Hirsch family to visit the rooms that were to be adapted on the first floor of the Pilsner house at 6 Plachý Street. In 1930, Martha Hirsch reminisced about this first visit in a letter to the Schroll publishing company, which was preparing a monograph for the architect’s sixtieth birthday: ‘The architect Loos visited the apartment that was to be arranged for us in February 1907. During his first visit, after briefly looking around, he made a quick sketch – I believe it was on an old envelope – as to how the apartment was to be altered and arranged. Later, nothing was changed in that sketch: everything was executed the way Loos had conceived it during those first fifteen minutes...’ This way of proceeding, as confirmed by an eyewitness and many of his other clients, was quite typical of Loos. Likewise, Loos usually established very good relations with his patrons, who often became his close friends. Throughout his life, Loos could rely on these friendships during financial difficulties, above all during the last months of his life. Often, Loos’ clients actively promoted his work and modern outlook, and recommended him to their friends for commissions.

In a similar manner, Loos supported his younger friend Oskar Kokoschka, whom he recommended to his own clients, sometimes virtually compelling them to serve as his models. It was not unusual for the customers to dislike the portraits and refuse to buy them – which perhaps will not seem surprising if we compare Kokoschka’s oil portrait with a pencil drawing of Martha Hirsch. To support the hard-up artist, Loos frequently bought the rejected works himself, and thus eventually became an owner of some of the most important of Kokoschka’s paintings. It was common for Loos’ first building project in a new city to attract further commissions. The Hirsch apartment, considered to be the most important of Loos’ works in Pilsen, is an illustrative example. The same year (1907), Loos was also entrusted with the design of the apartment of Otto Beck.

The Hirsch and Beck families were related. Wilhelm Hirsch and Otto Beck were cousins, partners in the wire-manufacturing company and neighbours. Loos was to realise similar projects for his circle of friends in Pilsen into the late 1920s. The Pilsner apartments of Hans and his brother Leo Brummel, as well as those of Dr. Josef Vogel, Leopold Eisner, Willy Kraus, and Hugo Semler were all designed by Loos within a span of three years. Later, he was also commissioned to design the apartment for Martha and Wilhelm Hirsch’s son Richard, also in the house at 6 Plachý Street, but on the street side and on the second floor. Thus, even as an adult, Richard could continue to enjoy his accustomed ‘Loos environment’. At the same time, his parents asked Loos to conceive a new ‘bay window’ room in the apartment that had served them, unaltered, for almost 25 years.

For Loos, an architect was a ‘mason who had studied Latin’. But he himself was also a ‘tailor’ who adapted the apartments of his clients to their physical and psychological needs, their character, and lifestyle. The future inhabitants, including the Hirsch family, willingly accepted his ‘bossiness’. Wilhelm had met the architect only briefly, but Loos seems to have evaluated his client quickly and was able to immediately make appropriate suggestions. In fact, if the creation of a sketch in fifteen minutes is astonishing, so is the unrestricted acceptance of such a procedure. And what is the outcome of that short but fruitful time today? The apartment was destroyed; only photographs and descriptions can give us some information.

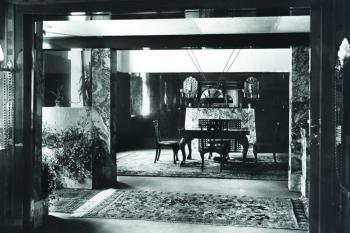

As was already mentioned, the project involved reconstruction of the second floor and the garden wing of a three-storey high apartment building from the late nineteenth century. The five-room apartment necessitated extensive structural changes to allow for the creation of two separate guest rooms and a spacious area for entertainment. In addition to the common areas such as the bedroom, children’s room, kitchen, hallway, and rooms for the personnel, Loos also created a sequence of another three rooms – two large, one small – that were intended as a dining room, buffet and a music room. To enlarge the visual impression, the dividing walls separating the three rooms were removed, except for the thin pillars on each side. The three spaces were then individually decorated using different materials. Dark mahogany was used in the dining room, precious marble from Skyros for the buffet, and light cherry wood in the music room and in the subsequent enlargement of the alcove. As much as possible, furniture was replaced by built-in closets, buffet-like consoles, and built-in vitrines. These not only gave an impression of spaciousness, but created many surprising and charming vistas. This is not the place for a more detailed description of the apartment, which can be found in the bibliography cited in the appendix. In addition, one should only mention the bedroom, decorated in light maple. Loos presented it in an exhibition more than twenty years later, when it could still be regarded as modern. He was proud that his creations were timeless and intentionally chose one of his earlier works for the exhibition. This timelessness of his works was recognised by his clients and sometimes remunerated. For instance, Paul Khuner, the owner of a food company, sent Loos a second honorarium decades later, saying that the timelessness of his apartment made a renovation superfluous and therefore saved him money. When his clients moved abroad, Loos’s creations were frequently moved too, despite the difficulties caused by the adjustment of fixed elements.

Nothing has remained of the former magnificence of Hirsch’s apartment. The free-standing elements ‘evaporated’ during the war, and the built-in fixtures, wainscoting, as well as the overall impression of space, were all destroyed during the alterations precipitated by the transformation of the apartment into a kindergarten after 1962. The vast majority of the installations in Loos’s apartments (estimated at about three hundred) suffered the same fate; today we can only gain an idea of a few of them based on photographs. Yet Loos himself believed that the impact of his complicated spatial creations could not be approximated, let alone transmitted, by a two-dimensional picture. The component of colour also completely disappears in black and white photographs. However, just as Loos attached a great importance to the three-dimensionality of his concepts, he also assigned a key role to the colours of the materials used. It was only the experience of the whole that could push one’s imagination to its very limits.

THE APARTMENT OF RICHARD HIRSCH

It is almost a miracle that in the same house, but looking onto the street and situated one floor higher, another of Loos’s apartments survived not only the war, but also the turbulent years and oppressive regimes thereafter. This considerably smaller apartment remained unknown and unprotected until fairly recently. The survival of this hidden treasure was further threatened by an increased possibility of its sale, reconstruction or other alterations as the years progressed.

At the time, nobody knew that the entire interior had survived the worst threats. The owner of the apartment had other plans for its individual rooms, and so decided to sell the whole of the original interior. Likewise, it is a miracle that the interior has now reappeared, perfectly restored, in a house in the Josefov district of Prague. In Pilsen, it had served the needs of a bachelor as an integrated living space that extended over two windows on the street side. The multi-purpose room offered a space for both eating and studying: a built-in desk by the library or the alcove of the cocktail bar. In Pilsen, this living room was connected with the bedroom.

As a bachelor apartment for a wealthy student, the space included no kitchen. A cook named Ema lived in a small flat on the same floor, and she both prepared the meals for Richard, and maintained the cleanliness of his apartment.

Here, although in a compressed form, we can find the same functional program that Loos applied in his residential houses and apartments. In the smallest, yet still spacious room, we can observe a maximum of functions skilfully combined together to create an impression of perfect unity. There is a dining area, a built-in desk for studying, a library, as well as an intimate seating area with a built-in cocktail bar.

In a reduced area and on a smaller scale, one experiences the same feeling for space as in the spectacular Villa Müller. Of course, this bachelor apartment is lacking the ‘female’ element so gracefully conceived in the Villa Müller. The planned wedding of Richard and Marieluis Kornfeld has led to a bathroom reconstruction and kitchen installation in 1935 (after the death of Adolf Loos), under the supervision of Heinrich Kulka, Loos’ former collaborator. Marieluis, who is now in her nineties and living in Australia, recalls this detail in a letter, dated September 2011: ‘I am very glad that Vladimir Lekeš succeeded in saving the apartment designed by the architect Adolf Loos for my husband Richard Hirsch in Plachý Street 6, Pilsen, where we spent part of our lives together. I believe that the apartment will continue to serve the public in future, just like it does now.’

At this point, it is appropriate to provide a detailed description of this newly found work by Loos, and accordingly discuss its original situation in Pilsen first. Presumably, the reconstruction of Richard’s apartment was to be executed at a reasonable cost, and as fast as possible. As a result, we find here many fewer significant structural changes than those of the apartment of Martha and Willy Hirsch that Loos supervised twenty years earlier. Since such minor changes did not have to be registered officialy, and did not require a building permit confirmation, it is impossible to date the reconstruction precisely. Recently, Maria Szadkowska has found a plan of the proposed alterations of Richard Hirsch’s apartment. An undated older plan was evidently provided with a new cover sheet in 1935 and re-used for another reconstruction. We can see this fact clearly from the differing font and graphics of the former plan and the new 1935 cover page. At the time, such use of older existing plans was quite common, particularly when only minor changes were to be executed, as was the case in Richard Hirsch’s apartment, where only the bathroom was to be reconstructed in 1935. Even the destructive alteration of Villa Steiner in Vienna in 1950s was based on Adolf Loos’s original plan of 1910. Forty years later, its reconstruction demanded an entirely new plan.

Consequently, it seems rather likely that Loos made the first plans for alterations of Richard Hirsch’s apartment in 1927, as is also mentioned in a document by Bořivoj Kriegerbeck, one of Loos’s collaborators at the time. This explains why the plans show even the later changes in detail. Likewise, the aforementioned letter from the widow of Richard Hirsch confirms the dating. The new apartment was created by detaching two rooms from the large existing apartment, which had comprised almost the entire second floor. The small remaining area was used as a guest apartment, where Richard Hirsch’s cook lived. The thin half-stone dividing wall of the living room of the reduced – but still generous- floor area of the apartment was reinforced by an insulating wall, and the former door was closed off. In order to create a new entrance with a hallway, cloakroom and a bathroom, Loos separated half of the stairway landing and included it to the former adjacent hallway. Thus, the old apartment received a new entrance, which could be reached by a newly created covered entrance outside. Later on, the same type of entrance was created also on the floor below. The remnants of Loos’s installation are clearly visible, including the travertine limestone plinths, that were probably cut from the stones used for the new veranda of the parents’ apartment. Again, this fact strongly supports the claim for Loos’s authorship, as well as the dating of the apartment.

Ilse Günther worked as Loos’s assistant during this commission, sketching his designs and keeping an eye on the building construction on his behalf. Loos employed Ilse about two years earlier, immediately after her graduation from the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, where she studied under the supervision of Professor Berndl. Ilse knew Claire Beck, later the third wife of Adolf Loos, for a long time. They went to primary school in Pilsen together and were close friends ever since. Many years later, it was a chance meeting with Claire in Vienna that brought Ilse to Loos’s studio. Although she had already been promised work at Josef Frank’s studio in Vienna, she accepted Loos’s tempting offer to work as draftsman in his studio. Frank only encouraged her; as he said this was a once of a lifetime opportunity.

In fact, the future interior architect witnessed Loos’s work in action already as a child on the occasion of the reconstruction of the Becks’ first apartment. As she reminisced in an interview fifty-five years later, the reconstruction deeply affected her: ‘it was an exhilarating experience that motivated me to study interior architecture after secondary school.’ At Loos’s studio, Ilse worked under the constant supervision of Heinrich Kulka and participated in the building commissions by Khuner, Moller, and Müller, amongst others. Receiving a commission from Tristan Tzara, Loos even sent her to meet the artist in Paris. During those years spent at Loos’s studio, Ilse also experienced the Becks’ relocation to their new family home at Benešovo náměstí 2 (The Beneš Square) in Pilsen. She took part in drafting of plans of the apartment’s interior. Shortly thereafter, Loos revamped the Becks’ old flat in 12 Klatovská St. for Dr Josef Vogl and his wife Stephanie.

A few years later, work led Ilse Günther to Pilsen once again. This time she participated in Loos’s commission at 6 Plachý St., where the Hirsch family decided to build an additional veranda to their apartment. Simultaneously, an independent project arose that Ilse was to execute following Loos’s design, no longer under the supervision of Heinrich Kulka. This was the technical drawing of Richard Hirsch’s apartment interiors and supervision of the reconstruction. Loos believed that young Ilse was qualified enough for the job. Moreover, she knew the Hirsch family and Richard himself very well. Of course, the architect Loos always kept an eye on the project, and often intervened to ensure its execution fitted his vision. The above mentioned building commissions for Loos, in which Ilse Günther participated, took place between 1927 and 1929, the period during which the project for Richard Hirsch was also completed. Thereafter, Ilse continued to work independently. Already in 1929, the year that Claire Back married Loos, Ilse moved to Warsaw where she started working for a Polish architect.

Richard Hirsch’s commission cannot be dated to the exact month, but it can be determined that it occurred in the period between 1927, when the plans were first drafted, and 1929, when the design was executed at the latest. Ilse von Henning, as she was called after her marriage, described her work for Adolf Loos in an interview for the fine arts magazine Parnass in 1985.

The final execution did not follow the plan in one detail: the planned separation of the stairway landing was executed in a scaled-down variation. Consequently, the cloakroom was reduced in size (from 1935 a kitchen) and the entrance door to the Hirsch apartment was at the same alignment as the door to the newly covered outside balcony. This is still visible today; the two adjacent doors, like the light fixtures on the staircase, were designed by Loos and date back to the time of the alterations made in 1927. The frieze that runs along the ceiling followed the new lines of the wall, so that the harmony of the area was preserved. As far as the terrazzo tiled floor with its meander borders was concerned, the adjustment was not made.

The new entrance to the remaining apartment was achieved by the newly erected courtyard gallery. In a short description of the path through the apartment, it is possible to recognise Loos’s work even on the public staircase: the otherwise ordinary main door of the apartment was replaced by a newly conceived one. A smooth, white painted, two-winged door with glass panels included in each of the wings created a new closure from the public staircase. The door fillings consisted of small glass squares in double rows of five pieces each.

The glass squares extended across the width of the door above, and provided additional light to the hall leading from the entrance to the main part of the living room. The entrance does not seem to have been furnished in a noteworthy manner, except for the addition of the above mentioned travertine plinths. A plain wooden door leads into the living room. It is painted white on the entrance side and, like the rest of the interior, oak-panelled on the apartment side. To the left, there were the small cloakroom, and, opposite, the somewhat smaller bathroom with a bathtub, wash basin and a toilet.

Such an element is often found in the works of Loos, where he connected rooms with different functions and decor using doors. This process is especially striking in the case of the shop of Goldman & Salatsch (1909/10) on the Michaelerplatz in Vienna, where the space for the clients is decorated with precious mahogany, but the employees’ space is painted in white, as is once again visible after its restoration in 1990. In Loos’ decoration of apartments, most of the entrance halls are executed in soft white painted wood, matching their inferior level of importance. We can presume this was also the case in Richard Hirsch’s apartment. However, there is nothing that could prove this theory, as nothing – except the doors – remains of the entrance today.

The path of a person entering leads directly from the main door through the entrance, changing direction only once. Here, Loos uses an architectural device which had been in his repertoire for several years, and appeared in an especially sophisticated form in the American Bar in Vienna (1908), where an ‘S’ shaped change of direction was achieved in the most limited space available.

One enters the main room of this bachelor apartment- the living room- from its wider side. The visitor faces the window front at its full original height of 3.5 m. A ceiling beam, circa 30 cm thick, crosses the room lengthwise and thus divides the narrow part approximately midway. This creates two unequal halves with different heights of 2.37 m and 3.57 m. In the entrance area, the ceiling has been lowered by about 1.2 m. In most Loos’ projects, the entrance spaces have lower ceilings, which relate to their inferior importance within the general concept.

As a result, the moment of entering the superior living space with a higher ceiling becomes intensified. If necessary, a round light fixture recessed into the ceiling provided light here. A newly created door to the left leads into the bedroom. Formerly, the door of this room was wider, not at the same place and led directly into the dining area; it was thus closed off. Through another smaller door, one could reach the bedroom from the cloakroom. Again, these modifications are not included in the 1927 plan. A visual barrier in the form of a low wooden structure halfway into the room encouraged one to proceed to the main part of the multipurpose living room with its high ceiling. Since the built-in structure closes off only the lower part using fixed closets, the eye is already led to the last and the most inviting area – the sitting alcove.

Yet, before entering this area, one first experiences the main area surrounding it. Again, one finds spaces of varied functions. To the left of the two windows, there was doubtless a dining-room table; one can still find a built-in dish closet here. The low room divider underneath the ceiling beam disguised the air exhaust of an additional heater, which could be used to supplement the radiators of the central heating system. Opposite, two additional drawers for tableware and silverware were hidden behind the doors of the room divider of the sitting alcove.

Between the two windows oriented to the street, there is a bureau and a working area. The board that runs along the windows has been widened at this spot to a total of 70 cm. As such, it could be used as both a writing desk and a serving board for food. For dining, the built-in bureau that recessed into the outer wall could be closed off by a roll-shutter. In only one gesture, the chairs could be also put back to the dining-room table. As a result, the work space could be easily hidden, and would not interrupt the relaxed dining in a pleasant company.

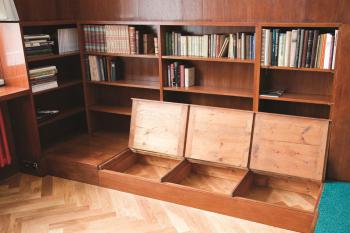

To the right, within the extension of the second window, there is a library. Built-in bookcases, covering half of the wall, accommodated the books of the passionate student. A comfortable easy-chair in the front was most likely used for relaxed reading or studying. A step in front of the built-in bookcases concealed three lockable spaces that allowed for discrete storage of additional items; today we do not know what these might have been.

Over another step, one finally reaches the most intimate part of this multi-purpose space. Although elevated, it is (with its height of 2.2 m) the lowest part, and at the same time the climax of the mise-en-scene. Although the niche is already visible from other zones, only inside can one experience the feeling of comfort that Loos’ art of interior design granted its owners. The central element is a rather low table surrounded by a U-shaped bench that also served as a storage chest. This simple installation is crowned by an attractive light fixture, suspended by its carrying electric cables. A short room divider closes off the longer right side of the bench, allowing for the installation of shelves within its immediate reach. The left side of the bench is shorter due to the built-in lockable compartments that are connected here. In the front, there is also an especially carefully conceived built-in cocktail bar for storage of bottles and glasses. Today, glasses that Loos designed in 1930/31 for the Viennese company Lobmeyr are kept here. Presumably, these come from the Müller House in Olomouc, or were in the possession of Paul Engelmann, a student of Loos.

Above the table, an attractive suspended round light fixture is mounted, whose ceiling plate also serves as a vent that can be regulated. Located in the middle of the grid formed by narrow ceiling beams, this device allowed for ventilation of cigarette or cigar smoke, and thus provided breathable air in this rather confined space. Usually, Loos would use an open fireplace for this purpose, however here such an installation had to be reconfigured due to the limited space available.

Despite having complete seclusion, a person seated in the niche can still see the entrance area, forming a safe space for watching without being seen. Again, this is a design element that Loos repeatedly applied in many of his works, perhaps with the greatest virtuosity in the Villa Müller in Prague. From a single room, the architect has created a sequence of several harmoniously interconnected individual spaces that, in spite of their visible separation, form a generous and a uniform volume.

INTERIOR DESIGN

Adolf Loos always offered different levels of economic cost for his projects, depending on the furbishing of the interior. However, just as a tailor uses cloth of different quality with the same care, the differences in price depended only on the materials used, not on the execution itself. He applied the wide range of different price categories either to differentiate the importance and value of the individual rooms, or simply to meet the client’s wishes and financial demands. Even without economic restrictions, he always remained thrifty while choosing the materials and deciding about expenditures. However, the final results never reveal this, as Loos respected the innate nobility of whatever materials were used. His ribbon buildings, designed immediately after the war for demobilised soldiers without financial means, but capable of performing the construction themselves, can serve as an example. These were not clad in precious marble, but realised with the simplest of means - and yet their creative spatial conception (Raumplan) ensured that they would look modern and elegant. Loos was proud that his works always seemed more expensive than the actual execution permitted. As he himself admitted, he owed many of his commissions to this very fact.

The furnishings of the apartment for Richard Hirsch differed from that of his parents not only in terms of the space available, but also in the amount of money at disposal. Times had changed, and it was inappropriate to offer a young student a life in too luxurious an environment. Still, he was not given the lowest category of interior furbishing available, but a somewhat more upscale version in oak. The advantage of using oak was not only its greater affordability, but also the fact that, thanks to its solidity, it would not suffer too much during the years of everyday use. Oak is light-resistant, durable, and can be easily buffed and restored. In those uncertain times, it was also of no temptation to thieves, unlike the highly valuable marble. We owe the survival of this apartment without any major losses to all of these factors, and of course, a good portion of luck.

The entire room is surrounded by a 1.3 m high wainscoting, which creates a continuous horizontal structuring line. The ceiling beams were used sparingly, only in the entrance and above the sitting area. The surface of the wainscoting is smooth and waxed. Almost along the entire length of the apartment, we can find built-in elements appropriate for their respective location and use. The insides of the back sides of the closet doors were executed in a more economical mahogany veneer. White glass shelves were placed in areas where liquor bottles or drinking glasses were stored. The floors were left in oak in the entire area, even under the podium of the sitting area that was covered by a green wall to wall felt carpet. All the doors from the entrance to the bedroom were changed to match the wainscoting, and new light fixtures were created. The costs were adequate; the execution certainly was not done in a “cheap” manner, yet without ostentation. One can see the involvement of the architect in every small detail, as well as in the general concept. Without hesitation, one can say that this work, executed twenty years after the Hirsch apartment and thus belonging to a later period in Loos’ career, follows the concepts of his earlier project, just like most of his later works.

Unfortunately, we can only guess what other furniture was created for this student apartment. Certainly, there were standard oak pieces that Loos frequently used in his designs, and would have once again employed here. The dining-room table was probably round-shaped and extendable, whilst the chairs could have been copies of the Chippendale collection, upholstered in leather or, less likely, in English linen. Fortunately, several original light fixtures have been preserved. Made exclusively from brass, with some nickel plating (as was the custom at the time), and glass, they all attest to Loos’ attentive and careful design. The above-mentioned light fixture in the sitting area is particularly interesting. Had it not been discovered by a chance in the attic of the house at 6 Plachý Street, one could not have conceived its shape and technical execution. It consists of two detached circles, with four exposed light bulbs attached to the lower of the two: one can light them individually by pulling a little chain; all of them can be lit at once by a separate switch. There is no visible power supply; hidden electric cables run along the four suspension cords, connected to the ceiling only by the hooks and the metal parts. This is an elegant, albeit daring solution that presents a certain risk during cleaning, even if the supply of 110 volts is switched off. The upper brass circle situated above the light fixture is projected onto the ceiling, and the 360° vent in the middle allows for a regulated aeration, since smoking was permitted in this interior.

The ceiling light in the entrance area is also round. However, simpler white glass is used here, providing a pleasant subdued light. The only wall light fixture is a modern version of the popular lights of the turn of the century. Nonetheless, the glass sticks of the semicircular cylinder are not suspended as would be the case in its earlier prototypes, but attached to the upper and lower brass plates, which effectively avoids the tinkling sound created by the glass sticks when touching each other in the breeze.

The various switches and wall sockets were also executed with a great care. The dark brown Bakelite discs are embedded in bevelled glass-cut rectangles. This functional and yet an aesthetic and elegant solution, has lost nothing of its usefulness today. The same thoughtful and well-crafted execution has reflected in other details, including the plated door fixtures or the countersunk handles of the closet doors. At present, an octagonal mechanical clock can be found here, similar to the electrical and larger one in the Strasser house in Vienna.

It is possible to assert that the apartment of Richard Hirsch has a remarkable interior, with solid and carefully considered design intended for a young man, who could flourish in this environment, without unnecessary impediments to his life-style or his studies. Even today, when entering this space, one is overwhelmed by a spontaneous feeling of well-being.

CONSERVATION

All but the built-in pieces of Richard’s furniture were lost. These and the wainscoting, with the exception of the U-shaped bench and the room divider closing it off, have been fully preserved. Despite the different lifestyle of later inhabitants of the apartment, the furniture’s practical and durable design did not necessitate its removal or alteration. Naturally, the original carpet had been replaced. Of course, one can see many traces of further use of the furniture that indicate negligent care. However, one cannot accuse its users of ignoring the value of this interior, especially in light of the complete destruction of the parents’ apartment.

It cannot be determined whether the entrance hall contained any built-in elements, but it is quite likely that the entrance door, the two upper windows and the travertine bases were not the only changes Loos made here. Nothing visible has remained of the original wall paint, or of the wallpaper that probably covered the walls of the sitting area above the wainscoting.

RESTORATION AND NEW INSTALLATION

The interior of the Richard Hirsch apartment has been moved to another apartment of approximately the same size in Prague, close to and overlooking the Jewish cemetery. The street-side room was marvellously suited for its new Loos interior and required only minor adaptations. The only difference from the original situation was that the street side of the room was about one meter longer, and thus the wainscoting and the main beam had to be lengthened. Otherwise, everything was set up and installed as it originally had been in Pilsen. It is worth noting that even when apartments’ interiors were moved under the supervision of Loos, some adjustments and even substantial alterations had to be made.

All parts of the interior were carefully examined and restored before they were put in place. Authentic techniques and the use of original materials were respected whenever replacements proved to be indispensable. This was the case during the replacement of the lost room divider of the niche, and the lengthening of the ceiling beam and the wainscoting along the longer walls. Due to visible marks on the wood of the wainscoting, it was possible to reconstruct the bench with great precision. In the meantime, surviving historic photographs allowed for a duplication of the English linen bench covers. This research method was also used when treating the floor covering. Several missing ornamental fittings were copied from preserved originals, as was the chandelier in the main room. Surviving light fixtures were restored, small missing parts were replaced, and the niche chandelier was hooked up according to its original arrangement.

The missing pieces of furniture were replaced by originals of equal function, and additional pieces have been acquired. For instance, a collection of chairs and a table were repatriated from England, where the original owner of the Rosenfeld house (designed by Loos in Hietzing in Vienna) had shipped them before the outbreak of the war. Once, Sigmund Freud, a welcomed guest of the Rosenfeld family, sat on those very chairs.

A sensitive, meticulous and labour-intensive treatment thus made it possible to save this rare example of one of the few remaining interiors by Loos, which would otherwise have almost certainly been destroyed. Today, the Pilsen interior created for Richard Hirsch serves as an art gallery and an auction house in Prague. It is not only a museum; the interior as a whole has a new purpose, and thus a new life.

(Professor Burkhardt Rukschcio, the world´s most important expert in the work of architect Adolf Loos)

Autor:

Burkhardt Rukschcio